We’ve written before about specific candidacy building opportunities, and explained how they can help prepare you for college. As college admissions become ever more competitive, students are looking for better and more impressive activities to help them stand out to admissions officers, and to help you in this quest, we’re presenting some truly great options for your activities.

In this article, we’ll be exploring FIRST Robotics, a STEM competition with extensive candidacy building opportunities. We’ll cover what the program is and how it works, how it helps with building candidacy, and show how it helped a past student in their successful application to Cornell. Let’s get started!

FIRST Robotics

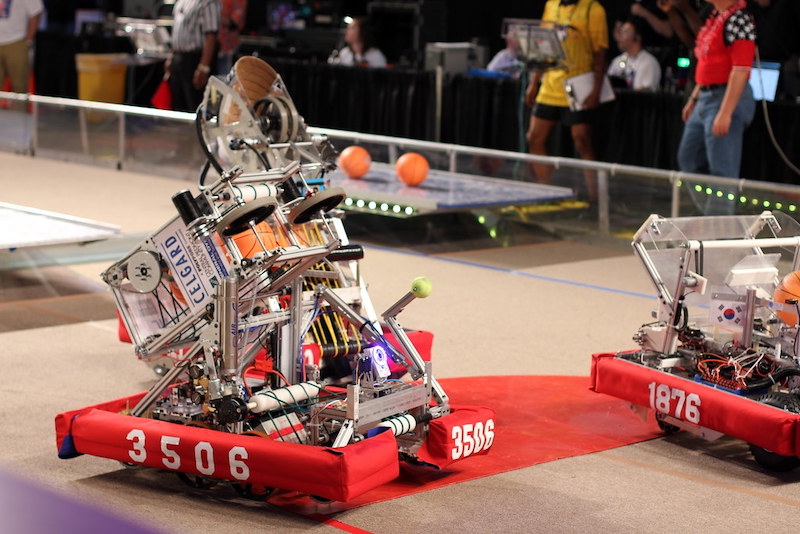

For Inspiration in Recognition of Science and Technology (FIRST) Robotics is a competition for students wherein they build a robot in order to compete in a variety of challenges. The structure of the program is unique, so we’ll go into some detail. We will be focusing on FRC, which is for students in grades 9-12. They offer additional competitions for younger students interested in robotics.

The primary goal of the competition is to get teams of students to learn hard and soft skills, for engineering, design, business, management, leadership, and cooperation. To that end, all work is done by students. While coaches and mentors may advise or lend expertise to help answer questions, the idea is that all of the work will be done by students themselves.

The work in question is building robots to compete in a series of challenges. These are large robots, weighting more than 100 lbs, and the contests are designed to reward taking risks with design and implementation. The field is approximately half as big as a basketball court, and the robots are required to complete both autonomous and human-controlled challenges.

This is a year-round project, which runs from June through to the following May:

- June through August is the offseason, which teams use for recruiting and fundraising.

- September through December is the preseason, and is used to train new team members, improve the team’s processes from past years, and continue fundraising efforts.

- January is when the challenge is announced, with the final contest occurring in May. This period is when teams do the work of building and programming. After a reveal video of the challenge, students have 10 weeks to design and build a robot which can move 30mph+ and solve the listed challenges.

Teams raise budgets of $25-50,000 through fundraising efforts to support the construction of these robots. The teams are set up like businesses, with different students in charge of fundraising, outreach, design, and construction, and management to make sure each group stays on track.

Teams compete in alliances of three robots that they make themselves. Teams will scout all of the robots at the competition to decide who to ally with. The top eight alliances after a round-robin competition move on to a knockout tournament.

The most successful teams have longstanding practices and tradition, and work to improve their institutional knowledge each year. This includes recruiting and training new members, finding sources of funding, and understanding their own workflow, and building libraries of code and resources.

These teams are generally run as high school activities. Over 3,200 teams from 27 countries competed in the 2021-22 season. If there is not a team at your school, it is more than possible to start one. While you may not win in your first year, the skills you learn from competing are still going to be great for you.

How FRC Helps Your College Applications

FRC can help your college applications in several ways. First, just as an experience, it provides multiple opportunities to both demonstrate leadership and show off your passion for various STEM fields and applications. Leadership especially is something colleges look for in all of their applicants, with many of them requiring an essay specifically describing a time you were a leader.

On top of this, the amount of time required by FRC makes it a strong demonstration of your passion for the STEM field. Colleges want students with clearly defined passions which they have devoted large amounts of their time to. What the passion is should be unique to each student, and demonstrated through their activities. By its design, FRC serves this role well, allowing you to take on new responsibilities and learn new skills each year you participate.

Finally, and most directly, as a major international competition, doing well at FRC demonstrates your level of skill and accomplishment in a quantifiable way. While colleges accept qualitative data as well, being able to give direct evidence of your accomplishments, and third party verification of your skills, adds weight to what you have done.

An Example

To support the above point, we will now go over an example of a past Ivy Scholars student who participated in FRC, and show you how he used that material in his essays. These were quite effective, with the student ending up accepted to Cornell, where they are studying engineering.

We will provide the essay, and then go over how the student effectively described their experience.

Example Essay

Here is one way to tell this story: 107 to 43 and 102 to 85.

These are the scores my teammates and I achieved when we won our division at the FIRST Robotics Competition World Championships. They represent the fruits of our effort, but not the months of late nights at the workshop, elation of winning, or despair of losing.

These scores don’t show the time Jakob fell asleep on his laptop keyboard in the middle of our club meeting after plowing through multiple consecutive all nighters struggling to get the angle of the robot’s intake just right.

I know the importance of how we tell stories, because not only am I an engineer, but I am also the videographer for my robotics team. As an engineer, I am inherently focused on numbers and details. During the season, for instance, I spent hours-upon-hours in the workshop, meticulously designing an efficient electronics layout by painstakingly rotating each part until they fit like a jigsaw puzzle in a 3D modeling program. Then, during competitions, I spent hours hunched over a table fixing intake mechanisms as an audience cheered out of sight.

By the middle of the season, I was dreaming of electric sheep. Our robot ran amazingly, but I was blinded by tunnel vision. I saw only the number of cubes scored and the number of cubes dropped. Our team’s cries of joy and sorrowful pouts had no place in this story. In the end, I short-circuited, overloaded by the constant number crunching.

I needed a new perspective; thus, I volunteered as team videographer.

My first assignment was our first competition of the season. Confusedly fumbling with camera settings, I immediately struggled with filming “recap” style. In effect, I filmed everything: people on their phones, the team shuffling about, Sarah struggling to replace a wheel in the dimly lit crew pits. By the end of the event, I was exhausted– but, somehow, also reinvigorated.

Reviewing the fragmented footage at home, I faced a refreshing problem: unlike robotics, videography’s objectives were vague with an infinite array of subjective paths. I threw all the footage into Final Cut Pro and just played around, blending transitions between clips, randomly adding generic royalty-free pop music, and motion tracking to highlight parts of the robot.

The results were not magnificent, but I saw how moving simple elements changed the entire story. On Robotics, my role as lead programmer meant my sights were ever-focused on winning. As videographer, I was now effectively team historian, focused on every decision leading up to the final scores.

Knowing my videos would become the record of my team’s efforts, I watched dozens of robotics “highlight” reels to glimpse how other teams told their stories. I spent hours deliberating over minor color grades and practicing camera movement until I was confident about executing my vision. I played with smooth pans, color grading, and thrilling music. Slowly, I charted my individual vision of our shared journey.

Steadily, my ability to focus on everything other than the score improved. I used the gimbal walk– knees bent with steady arms– to follow Jack skipping after we won our second competition. I caught a closeup of Sophie’s face, red with anticipation, as she awaited the final score at State Championships. Finally, at World Championships, I snatched a wide-shot of Ethan reaching into the air trying to grab the confetti after our division win.

In the end, I was as proud of my competition recaps as I was of the winning robot I built with my team. Becoming videographer changed my perspective – literally. I went from focusing only on stats to considering the numerous small stepping stones on the path to success.

As an engineer, I’m invested in the narrative of numbers; as a storyteller, I focus on the world around us. As a person, I seek a balance between the two.

Essay Analysis

This is a personal statement, and as such is meant to tell the story of who the author is, and how their experiences have shaped them. In the example above, the entire essay is framed by the student’s experiences in FRC.

This succeeds in several ways. First, it shows off the student’s clear devotion to and skill at engineering. They never come out and say they love engineering, but they demonstrate it clearly; nobody works hours that long for something they don’t care about. Being the lead programmer on the team also shows off their skills in this area. While this is listed on the activities list as well, the descriptions here show the reader just how much this activity means to the student.

Next, the essay shows how the student can self reflect. Borrowing a line from Asimov (A+ reference by the way), the student conveys their burnout, and the essay then turns to how they deal with that by taking on new challenges within the team. Describing their shift to videographer shows how the student is cognizant of their own needs, and has the emotional maturity to handle them smoothly.

Their practice at videographer continues this, showing off how the student is able to adapt to new challenges. The initial setbacks of learning a new skill are shown, as is the student’s journey to mastery.

Finally, and overall, the essay shows off multiple sides of the student through the single device. They are both a skilled engineer and an artist interested in their vision. They are both a motivated worker and cognizant of their own limits. They are both capable of taking the initiative, and working with teammates towards a grander goal.

The goal of a personal statement is to show off who you are, and to tell admissions officers something about you. While this can be about almost any subject, picking one which you have devoted a lot of time and energy to, and which has allowed you to grow as a person, makes for good material. FIRST Robotics does this quite well, along with helping you to develop the kinds of skills colleges look for in applicants.

Final Thoughts

There are plenty of great ways for you to spend your time, and only limited hours in a day. While FIRST Robotics is not the right choice for every student, we did want to bring it to your attention as a great way for students interested in STEM to get some hands-on experience, and to show off their passion.

If you want help finding the perfect extracurricular or summer program for you, schedule a free consultation to learn about how our candidacy building service can help. We’re masters of helping students discover their passions, and connecting them with the opportunities they need to explore them fully.